|

|

Genesis

and Management of the Reserve

Additional

Protections

Habitat

Restoration

Enforcement

Challenges

References

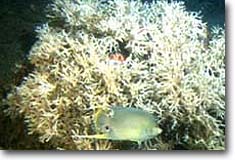

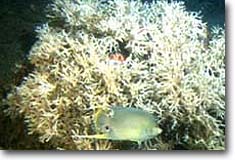

Fifteen to thirty miles off the east coast of Florida, a

series of submarine pinnacles and ridges extends from Ft. Pierce to Cape

Canaveral. Reaching as high as 65 feet above the sea floor, these features

act as a foundation for a habitat made distinct by the unique ivory tree

coral—Oculina varicosa. A slow-growing, delicate and branchlike

coral, ivory tree coral thickets often are associated with high

biodiversity because they provide ideal spawning sites for numerous

species, including economically important fish like several species of

grouper (gag, scamp, snowy and warsaw), black sea bass, speckled hind and

red snapper (NOAA, Ocean

Explorer, 2001).

|

Healthy

Oculina coral heads, such as this one on Jeff’s

Reef within Oculina Bank, stand three to four feet high and three to

four feet across. Such habitat creates “thickets” that are used by

diverse fish and invertebrate assemblages.

|

During the 1960s and ‘70s, hook-and-line fishers

frequented Oculina Bank and landed large catches of several species of

groupers. By the early 1990s, much of the habitat was destroyed, and fish

stocks appeared to be severely depleted. The ivory tree coral that

provided reef structure needed by many resident species had been decimated

in many places—an outcome believed to be the result primarily of

destructive bottom trawling, though other causes have been implicated (NOAA, Ocean

Explorer, 2001). With the habitat in ruins, fish spawning dropped

sharply. In an effort to protect what was left and perhaps repair the

damage, scientists moved to protect the remainder of the unique Oculina

coral habitat and reestablish corals and their associated fish

population.

Genesis

and Management of the Reserve

In 1975, scientists with the

Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution (HBOI) were conducting underwater

surveys of the continental shelf when they discovered that the high relief

pinnacles along the shelf were colonized by living, deep-water coral reefs

composed of Oculina coral. Ensuing studies investigated the distribution

of the coral, its growth rate, community structure, biological and

geological processes, and the effects of upwelling and bioerosion. Studies

also predicted the drastic decline in fish stocks and the destruction of

the coral (Reed,

2001).

|

A small sample of ivory

tree coral, Oculina varicosa. The coral is as fragile as it

appears and is no match for heavy objects such as anchors or

trawls.

|

Bottom trawling is believed

to be the major reason for the coral’s destruction. But other factors may

account for some of the dead coral. For instance, episodic coral die-offs

or extensive bioerosion may have occurred. In addition, it is widely known

that anti-submarine patrols during World War II frequently and liberally

employed underwater explosives in their search for German U-boats off the

coast of Florida. Such activity may have adversely affected the benthic

habitat.

Regardless of the causes for damage, many scientists

believed the area needed protection. In 1980, John Reed, chief scientist

in the Division of Biomedical Marine Research at HBOI, petitioned NOAA’s

National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the South Atlantic Fishery

Management Council (SAFMC) to protect the Oculina coral habitat from

further harm. Reed, who had conducted extensive research of the habitat

and was intimately familiar with the ecology of the bank, had published

numerous articles describing the distribution and growth of the coral, and

the diverse animal communities living among it (HBOI,

2001).

|

Gag grouper, one of the

most important commercial fish species in the southeast, taking

cover in Oculina coral. Populations of all grouper species

have been severely reduced on Oculina Bank, most likely the result

of habitat loss and overfishing.

|

In 1982, the SAFMC published

the Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for Corals and Coral Reefs,

which included a proposed action to develop, adopt and implement a fishery

management plan for coral and coral reef habitats within the areas under

the authority of the SAFMC and the Gulf of Mexico Fishery Management

Council. Among other objectives, the action proposed setting aside a

portion of the Oculina Bank as a habitat of particular concern (HAPC), a

designation that would categorize it as an area of special biological

significance worthy of stricter regulatory and enforcement activity (SAFMC,

1982). In 1984, the proposed action was finalized, and NMFS set aside

92 square miles of the 300 square-mile Oculina Bank as an HAPC (HBOI, 2001).

The new designation prohibited mobile fishing gear like trawls and

dredges, but it did not affect anchoring or weights used for bottom

fishing.

|

Approximate location of

Oculina Banks off the east coast of Florida. Here Oculina coral

"thickets" grow at depths of about 230 to 400 ft on a series of

pinnacles and ridges that extend from Ft. Pierce to Cape

Canaveral.

|

(top)

Additional

Protections

Nine years later (in

1991), damaged corals showed few signs of recovery. To encourage coral

recovery, NMFS and SAFMC proposed to establish the Oculina HAPC as an

experimental closed area—a much stricter designation. The action, which

became effective on June 27, 1994, prohibited all bottom fishing within

the newly designated Experimental Oculina Research Reserve (EORR). The

EORR was established as a 10-year experiment to determine if depleted

species, such as snapper and grouper, would rebound. The restrictions,

however, did not prohibit midwater or surface fishing from moving vessels

(SAFMC,

1993). The EORR will be eligible for reauthorization in

2004.

Just two years later, SAFMC implemented additional

protections for the EORR by prohibiting anchoring activities of fishing

vessels within the area. Fishing vessels could not drop anchors, grapples

or attached chains, which were known to damage or destroy the coral,

within the EORR (SAFMC,

1995).

By 1998, efforts were underway to amend the Oculina HAPC

even further. SAFMC was mandated by a 1996 amendment to the

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Management Act to describe and identify essential

fish habitat (EFH), including adverse impacts on such habitat, in order to

minimize damage to EFH resulting from fishing activities. In addition, the

agency was required to identify other actions that encourage the

conservation and enhancement of EFH (Magnuson-Stevens

Act, 1996). Because Oculina Bank was considered EFH needing additional

protection, SAFMC proposed extending the boundaries of the reserve by 60

square miles to provide a larger protected area (SAFMC,

1998). The amendment included creating two protected satellite sites

of three square miles each.

|

Oculina coral rubble. Currently, large areas of

Oculina Bank are in this condition. Note the faint outline of a reef

ball in darkness on the far right. Scientists hope that these

experimental structures will help to reestablish Oculina habitat.

|

The proposed change

met with some opposition, particularly from the longline fishing industry,

which feared that the new rule would be unduly burdensome. Some detractors

argued that the proposed expansion included large areas that did not

contain Oculina coral— only flat mud bottom habitat. Restricting these

areas would not help the coral habitat, but it would affect bottom

longline fisheries for tilefish, grouper and shark, according to the

commenters (Federal

Register, 2000).

However, NMFS reasoned that including the

non-coral habitats within the HAPC would create “buffer zones” around the

coral habitat. The buffer zones would reduce the likelihood of accidental

incursions and would simplify enforcement activities, according to NMFS.

In addition, NMFS noted that previous rules established similar zones

around areas fished by the rock shrimp and calico shrimp industries. The

agency argued that the new rule would further streamline fishing

regulations (Federal

Register, 2000).

Finally, some commenters contended that the

amendment was overly broad and exceeded the agency’s authority. NMFS,

however, believed that its legal authority under the Magnuson-Stevens Act

was broad enough to restrict activities, fishing and otherwise, that may

adversely affect EFH. Thus, in July 2000, the new rule took effect. All

gear prohibitions and anchoring restrictions that were applicable within

the old boundaries applied to the expanded boundaries and the satellite

sites as well (Federal

Register, 2000).

(top)

Habitat Restoration

Since 1995,

scientists have been trying to reestablish the fragile, slow-growing

Oculina corals by deploying concrete substrate to encourage colonization.

In 1996, they began by deploying clusters of concrete “reef balls”

throughout the reserve, hoping that the corals would attach, settle and

grow. Some were deployed with live coral already attached, and some were

deployed bare. Three years later, the scientists discovered that live

coral remained on some of the balls. On others, the coral was stripped

off, and only one reef ball deployed without coral attached showed coral

recruitment (NOAA, Ocean

Explorer, 2001).

|

In September 2001, a

grouper shows interest in one of 105 reef balls a year after they

were deployed on Oculina Bank. On the right is an arm of the

submersible Clelia, used by scientists to examine progress in

this effort to reestablish Oculina habitat and the associated fish

and invertebrate

communities.

|

In 2000, a

different type of reef ball—dome-shaped equipped with holes through which

fish could swim—were deployed. The balls, which were similar in size and

shape to an Oculina coral colony, were released with live coral attached.

In the summer of 2001, explorers found that several fish species,

including groupers, amberjacks, snappers, angelfish, butterflyfish and

small basses, had colonized the structures—an encouraging sign of initial

habitat restoration. Researchers also observed more gag and scamp grouper

at the southern end of the EORR. Just 10 years ago, researchers saw no gag

grouper, fewer than 10 scamp grouper, and very few amberjacks in the same

area (NOAA,

Ocean Explorer, 2001). Though too soon to tell how successful the

coral reestablishment efforts will be, scientists are optimistic about

their initial restorative efforts (NOAA, Ocean

Explorer, 2001).

Enforcement Challenges

Because the EORR is isolated and relatively distant from

shore (17 mi), consistent enforcement of the fishing and trawling ban has

been difficult. Enforcement authorities are aware that illegal shrimp

trawling occurs in the no-fishing zone. Though spotter planes and

helicopters can survey the area, they cannot enforce the no-fishing zone

restrictions alone. If they suspect illegal activity, they must alert U.S.

Coast Guard surface vessels, which may not be available or in an

advantageous position to respond immediately. Authorities believe that

much of the illegal fishing activity occurs at night, making enforcement

more difficult. Also, aerial surveillance missions often cannot

distinguish between legal fishing activities, such as trolling for pelagic

fish, and illegal anchoring and bottom fishing. Moreover, enforcement

officers cannot determine or prove where fish were caught after a

suspected boat returns to port (Reed,

2001).

|

This image shows the likely impact of

bottom trawling on Oculina Bank. The linear mounds of coral rubble,

shown on the right, are created immediately adjacent to the track of

the trawl.

|

To aid enforcement efforts, the SAFMC recently voted

to require vessel permits and the use of vessel monitoring systems (VMS)

in the calico scallop fishery south of the Georgia-Florida border. The VMS

allows enforcement authorities to pinpoint a vessel’s position in relation

to the boundaries of the marine protected area (Reed, 2001). By

using the VMS and conducting random surveillance missions of the protected

area, as well as implementing educational efforts aimed at both commercial

and recreational fishers, SAFMC hopes that self regulation will improve

and the Oculina habitat eventually will recover.

References

Fisheries of the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and South

Atlantic; Essential Fish Habitat for Species in the South Atlantic;

Amendment 4 to the Fishery Management Plan for Coral, Coral Reefs, and

Live/Hard Bottom Habitats of the South Atlantic Region (Coral FMP).

Federal Register, June 14, 2000 (65, 37292-37296). Washington, DC: U.S.

Govt. Printing Office.

Harbor Branch Oceanographic

Institution (HBOI). 2001. Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution’s Web

site. www.hboi.edu.news/features/oculina.html.

Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and

Management Act. Public Law

94-265 (as amended through October 11,

1996). http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/sfa/magact/

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

2001. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Ocean Explorer Web

site.

Oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/islands01/background/

islands/sup6_oculina.html.

Reed, J. K. In press. Deep-water Oculina Coral Reefs of

Florida: Biology, Impacts and Management. Hydrobiologia. Dordrecht, The

Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC).

1998. Amendment 4 to the Coral, Coral Reefs and Live/Hard Bottom Habitat

Fishery Management Plan. Comprehensive Amendment Addressing Essential Fish

Habitat in Fishery Management Plans of the South Atlantic

Region.

South Atlantic Fishery Management

Council (SAFMC). 1995.Amendment 3 to the Fishery Management Plan for

Coral, Coral Reefs and Live/Hard Bottom Habitats of the South Atlantic

Region.

South Atlantic Fishery Management

Council (SAFMC). 1993. Amendment 6, Regulatory Impact Review, Initial

Regulatory Flexibility Analysis and Environmental Assessment for the

Snapper Grouper Fishery of the South Atlantic Region.

South Atlantic Fishery Management Council (SAFMC).

1982. Fishery Management Plan Final Environmental Impact Statement for

Coral and Coral Reefs.

(top) |